In the run-up to what could prove to be the most spectacular fortnight in the history of El Clásico — the great rivalry between Real Madrid and Barcelona — the whole world has caught Barcelona-itis.

Or near enough, anyway. The Passing Game — you can hear the capitals when someone is really pontificating — of the Blaugrana has brought football to an entirely new place, one of endless strings of one-touch builds, wing isolation and a premium on possession and letting the ball do the work.

The ball, after all, has no lungs. It will never get tired.

[inlinenode:318545]However, short of pulling a Xavi or an Iniesta, let alone a Messi, out of your hat, there’s little hope of even approximating Barcelona’s style. It’s the end product of a system that’s been percolating for 40 years, and driven by three of the greatest talents ever to play the game.

The futility of that errand is best summed up by this fact: In one-on-one situations, Lionel Messi beats his man nearly 90 percent of the time. No one in Spain is within 20 percent of that, and it’s likely that no one in MLS is, either. He forces you to shade to his side defensively or risk being on the end of a highlight that’ll be must-see TV the world over.

Thus by virtue of merely having Messi on the field, the opponent’s shape is already broken, allowing Xavi and Andrés Iniesta time and space to go to work.

That’s a unique luxury. Hopefully there are some 12-year-old kids in MLS academies who’ll do the same here a half-decade hence. But in the here-and-now, Barça are inimitable.

Their theory, though, is not.

Leave aside the technique and one-on-one aspect of their success, and what becomes most apparent is that Barcelona (and, quite often, Spain) win games by controlling the central midfield. And they do that not just with technique and skill, but with numerical superiority.

In Xavi and Iniesta, and their water-boy Sergio Busquets, both Barça and Spain have three pure central midfielders. Often times Spain will field Xabi Alonso as well, adding a fourth and pushing Iniesta higher into the attack.

This “extra” central midfielder has become a key in the modern game, and you can tell a lot about the mentality of a team by where they take that third central midfielder from.

The standard practice is to sacrifice a forward and, as a consequence, put more pressure on your wingers to get into the box and the fullbacks to overlap. A good MLS example of this is found in Dallas, where MVP David Ferreira plays as a third central midfielder in front of Daniel Hernandez and, most recently, Andrew Jacobson. Meanwhile, Milton Rodriguez is left to plow a lone furrow up top.

Obviously it worked for FC Dallas in 2010 (with Dax McCarty in Jacobson’s role) and it will again in 2011, I suspect, once they’ve worked out some personnel-related kinks.

Because Ferreira has such a nose for goal and FCD have a never-ending supply of speedy, skilled wingers and fullbacks, they’ve been able to drop the second striker and not suffer much in terms of creating goals. They also have a central midfield trio with complimentary, rather than overlapping, skillsets.

And while they’re not always dominant in the center of midfield, they’re never dominated themselves.

If that’s the standard – or close to it, anyway, since no two approaches to a tactical problem are ever the same – then what Real Salt Lake do on a weekly basis is the exception.

RSL pin their midfield movement to playmaker Javier Morales. What he's doing determines the position and priorities of the other three midfielders.

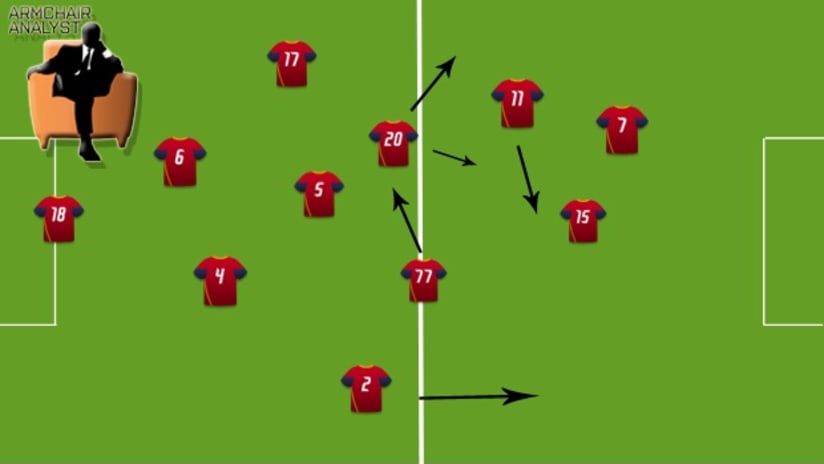

[inlinenode:333901]The Argentine enganche is always listed as a central midfielder, but often picks up the ball nearer the flanks (at right). That’s anachronistic in the modern game, especially given RSL’s mandate to keep the ball on the floor and control possession, since, nominally, it would leave his team numbers-down in the center of the pitch.

But RSL are able to compensate and actually capitalize by instantly adjusting their shape to where Morales is on the pitch and what he’s doing, and almost never find themselves caught short in the middle of the park.

If Morales is out by the left touchline, which is his favorite place to operate, Andy Williams or Ned Grabavoy will slot forward from their “right” midfield spot and become the orchestrator. Will Johnson, usually the “left” midfielder (and yes, I’m using quotes for a reason, as none of the three are wide midfielders in any but the loosest definition) will then either loop around the flank if Morales dribbles toward the central channel, or pinch centrally if Morales makes a vertical run.

Either way, the end product is three midfielders in the central channel with fullback support and two true forwards still plying their trade in-and-around the 18. It's Johnson, Kyle Beckerman and either Williams or Grabavoy if Morales goes vertical; or, if Morales cuts inside, he joins Beckerman and Williams/Grabavoy with Johnson becoming a runner.

The downside to these tactics, of course, is that it takes several years of practice and familiarity to achieve the level of cohesion RSL display. Most teams, and most fanbases, don’t have that kind of patience.

Real Salt Lake did, and now they’re in the CONCACAF Champions League finals. And Barcelona’s front office certainly had patience and kept the faith with the talent they’d developed, and they’re pretty heavy favorites to head to their own Champions League final (and beyond) as well.

Moral of the story? Have patience with your team’s early-season struggles. And enjoy The Passing Game – and all the innovation it brings with it – whenever you get the chance.

Matthew Doyle can be reached for comment at matdoyle76@gmail.com and followed on Twitter at @MLS_Analyst.